When I think of the paleo diet, I think of Christianity - many variations built off of the same basic tenets. With Paleo, you've got avoidance of grains and dairy, and from there you get a lot of variation - whether modern oils are allowed is questionable, many don't consume but some are okay with legumes, some avoid nightshade vegetables, some worry about lectins, some worry about high PUFA intake, some worry about phytates, some eat high carb foods like tubers. Given this variability, Paleo falls into a feelings pool where most fad diets for me fall - it's a religion, not a prescription.

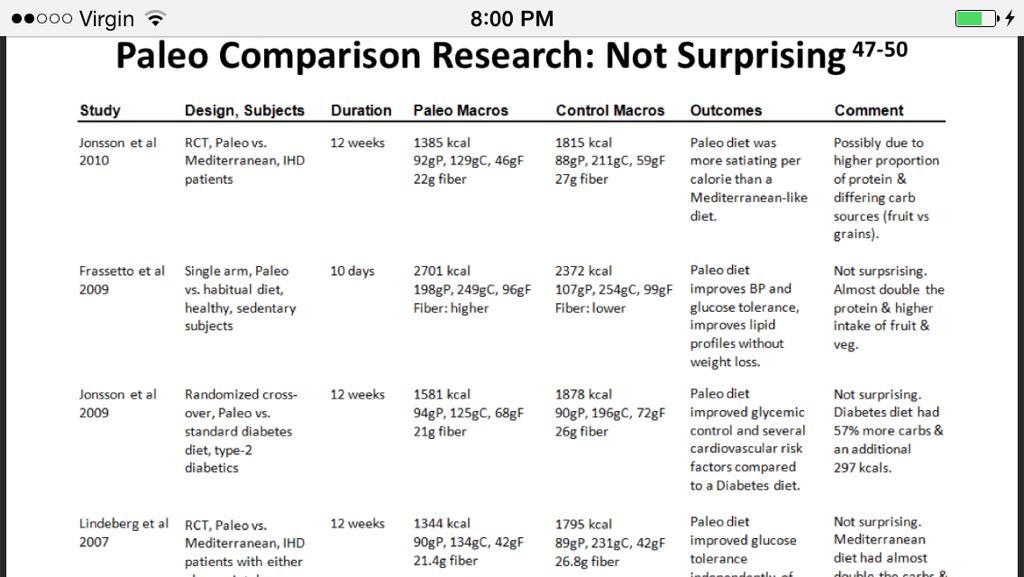

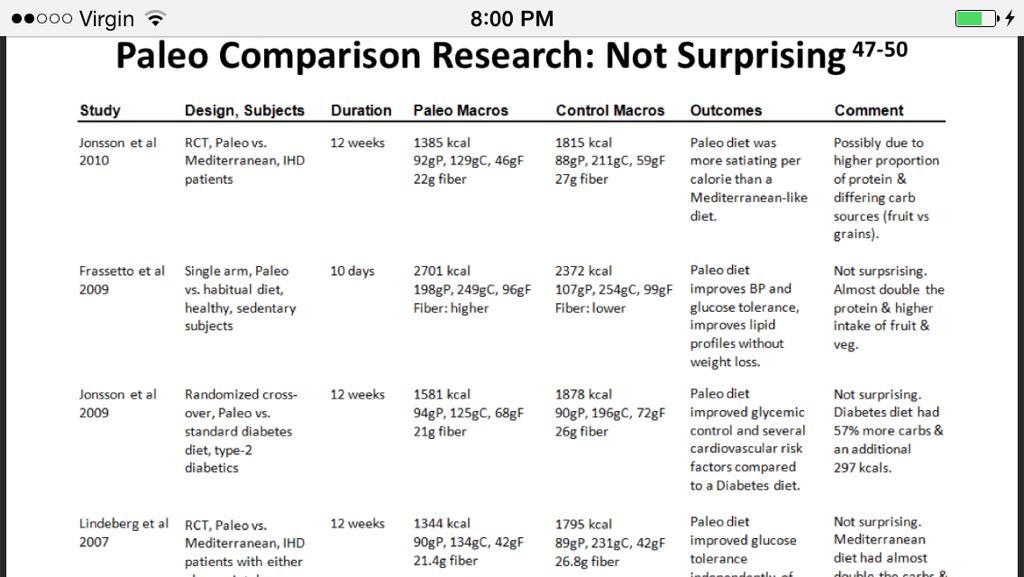

This variability in dietary trials of the Paleolithic diet was pointed out by Alan Aragon in his NSCA presentation on the topic:

As Alan notes, for a diet that claims superiority due to its removal of grains and dairy, no study has really isolated these factors.

I was particularly surprised to see a recent meta-analysis of the Paleo diet in AJCN this upcoming issue. The meta-analysis had a total of 159 participants across 4 trials, with nearly half of the n coming from one trial (for reference, an upcoming JACC Mediterranean diet trials meta-analysis has ~11,000 participants). They didn't include all of the trials Alan discussed above, and included 2 newer ones, Boers and Mellberg.

This variability in dietary trials of the Paleolithic diet was pointed out by Alan Aragon in his NSCA presentation on the topic:

As Alan notes, for a diet that claims superiority due to its removal of grains and dairy, no study has really isolated these factors.

I was particularly surprised to see a recent meta-analysis of the Paleo diet in AJCN this upcoming issue. The meta-analysis had a total of 159 participants across 4 trials, with nearly half of the n coming from one trial (for reference, an upcoming JACC Mediterranean diet trials meta-analysis has ~11,000 participants). They didn't include all of the trials Alan discussed above, and included 2 newer ones, Boers and Mellberg.

- Boers included 32 individuals in the study (Paleo n=18, Dutch diet n=14) that had 2 components of metabolic syndrome - The Paleo diet participants had a significantly worse metabolic profile at baseline (MetS score: 3.7/5 vs 2.7/5). The diets were supposed to be isoenergetic but the Paleo diet lost about a few lbs more over the 2 week study - very little about the two diets were well match (e.g. much higher potassium/protein/PUFAs (both n-6 and n-3) and lower in CHO in the Paleo diet). Food was provided and adherence was determined by via food records. We have no baseline dietary intake data - as we know from virtually all restrictive diets, they're a big change for people, whereas control diets often require little change. Not surprisingly, the more metabolically unhealthy 'Paleo' intervention group saw more beneficial effects on blood pressure and lipids - nothing about this study says that removal of grains/dairy are uniquely beneficial (the main tenant of Paleo). Note that this study saw no effect on inflammatory markers or intestinal permeability, two big accusations that many Paleo'ers make against grain-containing diets.

- Melberg is the longest Paleo trial with the most individuals. 70 post menopausal women with obesity were randomized to a Paleo diet or Nordic diet. The trial was registered and designed to look at a modified Paleo Diet (low carb, high protein) on liver fat, and body weight (secondary outcome). The Paleo Diet group was counseled to consume a diet of 30 percent protein/CHO and 40 percent fat. The Nordic group was to consume 15 percent protein, 25-30 percent fat, and 55-60 percent CHO. Unlike other versions of Paleo, refined oils were allowed (canola/olive). The self reported data suggests that the Paleo diet group increased protein a bit, but urinary nitrogen shows that they didn't. The Nordic group ended up reducing CHO, not increasing as they should have (they even reduced fiber intake from baseline #faileo) . Paleo'ers seem to have primarily eaten more fat from MUFAs/PUFAs. Looking at the self-reported nutrient intakes, we can see that changes reported at the 6 month point differ pretty drastically on some accounts compared to the 2 year point, strongly suggesting a lack of adherence. This is supported by differences in anthropometric measurements seen at 6 months between the groups but not at 2 years. The self reported data is hard to trust, when people are reporting having reduced more kcals from baseline during the times when individuals appear to be gaining back weight that they've initially lost. In this recent AJCN meta-analysis, only the 6month time point data are used. The main outcomes of this trial showed a greater weight loss at 6 months, and greater reduction of TG at the 6 and 24 months for Paleo'ers (note: the TG levels are all within normal ranges) - no significant effects were found for any of the metabolic and inflammatory markers measured. Essentially, two groups of dieters were given a prescribed diet, one highly restrictive and the other not, few seem to have adhered and the highly restrictive one lost more weight - put on your shocked face. In my personal research opinion, if you want to test the effects of a low-carb high protein Paleo diet, your control group should also be a low carb high protein diet, that is, if your goal is support the Paleo aspect of all this. Otherwise, there are specific nutrient content differences that likely explain the differential results.

The Meta-analysis finds improvements in waist circumference, triglycerides, HDL, blood pressure and blood glucose (though HDL and blood glucose weren't significant). Again, we're seeing pretty significant heterogeneity in the diets employed by both the Paleolithic diets and their respective control diets. Mellberg contributes largely to the effects on waist circumference, whereas Boers contributes very significantly to the effect on TGs (note that the MA doesn't show a funnel plot). All of these analyses are quite limited due to the meta-analysis analyzing changes from baseline - the appropriate method for analyzing RCTs is to determine differences between the treatment and control group, and factor in baseline differences in more robust statistical models (baseline diets aren't randomized and significant differences can lead to large effects not due to the treatment).

The actual meta analysis does an okay job of noting some of these limitations (e.g. very defensively discussing baseline imbalance), suggesting that more research is needed before Paleo nutrition can be considered in guidelines (though they seem to stress that interventions were similar, even if the diets consumed weren't). The authors conclude making fair comments that those with MetS likely will do better reducing some CHO and sodium intake, but oddly note the benefits of a lower n6:n3 ratio ( in their own analysis, they use Mellberg's 6 month data, where the Paleo group increased n-6's from baseline - none of the trials took erythrocyte FA compositions to confirm dietary intake data and support this claim; I also doubt the necessity of this ratio in a dietary pattern that emphasizes preformed LC-n3's aka fish).

To me, a meta-analysis is appropriate when you've got a relatively similar intervention across several studies (usually not a lot of pilot data) to get a substantial n. I've talked in the past how MA's in nutrition can often be inappropriate, given the multiple interventions that come with diet trials. This is one of those times. A short review discussing these 4 trials would've been substantially more appropriate than pooling together the data of 4 pretty different interventions, across substantially different time courses (2wks to 6months). If Paleo is going to try to claim the superiority of a dietary pattern that's low in grains and dairy, trials should be designed to show such things - as of now, we have none. The meta-analysis supports the idea that a Paleolithic diet in the short term can contribute to metabolic improvements, as can many dietary patterns. To get the results achieved by the Paleo diet, I'll stick to a high fiber, high potassium, low calorie diet and enjoy the foods that I like - if individuals want to eat 'Paleo' they certainly can, as long as it is well-planned (like seemingly all named diets). Paleo enthusiasts would be better off testing the benefits of grain-free diets and dairy-free diets, than sticking to a simple name that will get them quickly written off as a fad-diet - as I've discussed before, there's legitimate scientific questions about the role of grains/grain-free diets in health. I could nit-pick about their anti 'processed' foods arguments, or why evolutionary thinking about nutrition isn't totally appropriate, but i'll just defer readers to some of my past thoughts on thinking 'evolutionarily' about nutrition, here and here.

As a side note, the authors of the MA dismiss concerns about low calcium intakes from Paleolithic diets, based on the urinary calcium measures from Boers. I'm not convinced - calcium balance studies require being trapped in a metabolic ward, and precise knowledge of calcium intake, urinary and fecal calcium. Balance studies aren't even started until 7 days into the dietary study (when calcium intake has been consistent) to achieve a steady state - since we can't assume that individuals were consuming the exact same amount of calcium per day in the free-living trial, we shouldn't be drawing any conclusions about calcium balance from a single urine. While I agree that the low-salt content of the diet might reduce calcium excretion and improve calcium balance, a well designed trial should address this - not conjecture dismissing a legitimate concern.

Carbsane also covered this meta-analysis here. A recent letter to the editor was published highlighting a number of methodological issues with the analysis:

The actual meta analysis does an okay job of noting some of these limitations (e.g. very defensively discussing baseline imbalance), suggesting that more research is needed before Paleo nutrition can be considered in guidelines (though they seem to stress that interventions were similar, even if the diets consumed weren't). The authors conclude making fair comments that those with MetS likely will do better reducing some CHO and sodium intake, but oddly note the benefits of a lower n6:n3 ratio ( in their own analysis, they use Mellberg's 6 month data, where the Paleo group increased n-6's from baseline - none of the trials took erythrocyte FA compositions to confirm dietary intake data and support this claim; I also doubt the necessity of this ratio in a dietary pattern that emphasizes preformed LC-n3's aka fish).

To me, a meta-analysis is appropriate when you've got a relatively similar intervention across several studies (usually not a lot of pilot data) to get a substantial n. I've talked in the past how MA's in nutrition can often be inappropriate, given the multiple interventions that come with diet trials. This is one of those times. A short review discussing these 4 trials would've been substantially more appropriate than pooling together the data of 4 pretty different interventions, across substantially different time courses (2wks to 6months). If Paleo is going to try to claim the superiority of a dietary pattern that's low in grains and dairy, trials should be designed to show such things - as of now, we have none. The meta-analysis supports the idea that a Paleolithic diet in the short term can contribute to metabolic improvements, as can many dietary patterns. To get the results achieved by the Paleo diet, I'll stick to a high fiber, high potassium, low calorie diet and enjoy the foods that I like - if individuals want to eat 'Paleo' they certainly can, as long as it is well-planned (like seemingly all named diets). Paleo enthusiasts would be better off testing the benefits of grain-free diets and dairy-free diets, than sticking to a simple name that will get them quickly written off as a fad-diet - as I've discussed before, there's legitimate scientific questions about the role of grains/grain-free diets in health. I could nit-pick about their anti 'processed' foods arguments, or why evolutionary thinking about nutrition isn't totally appropriate, but i'll just defer readers to some of my past thoughts on thinking 'evolutionarily' about nutrition, here and here.

As a side note, the authors of the MA dismiss concerns about low calcium intakes from Paleolithic diets, based on the urinary calcium measures from Boers. I'm not convinced - calcium balance studies require being trapped in a metabolic ward, and precise knowledge of calcium intake, urinary and fecal calcium. Balance studies aren't even started until 7 days into the dietary study (when calcium intake has been consistent) to achieve a steady state - since we can't assume that individuals were consuming the exact same amount of calcium per day in the free-living trial, we shouldn't be drawing any conclusions about calcium balance from a single urine. While I agree that the low-salt content of the diet might reduce calcium excretion and improve calcium balance, a well designed trial should address this - not conjecture dismissing a legitimate concern.

Carbsane also covered this meta-analysis here. A recent letter to the editor was published highlighting a number of methodological issues with the analysis:

Comments

Post a Comment